The French government got me! They caught me driving by one of their speed cameras. Of course, the photo clearly shows that I was driving well below the speed limit. But what do facts matter when the real purpose is fundraising?

This ticket alleges that my car was traveling 97 km/h in a 90 km/h zone on the A6 down in Écully, just north of Lyon. Because there is a 5 km/h buffer to allow for error on posted speeds of less than 100 km/h (above 100 km/h, it would be 5%), this means I was formally charged with the crime of going 92 km/h in a 90 km/h zone.

I would never expect to have a good chance of success in fighting a ticket anywhere in the world. I’ve driven a lot, been ticketed, and fought tickets before. Interestingly, my tickets have been wrong more often than they have been correct. (My last photo citation showed somebody else’s car.) I am thus very aware of the uphill battle when wrongly ticketed, but I think it’s important to document these stories, even if we must live in places with such reduced liberté.

My case

I know society has a tendency to prejudge these situations (“Oh, he’s guilty, but he just wants to exploit some technicality. It’s a photo so it must be correct.”). I ask you to please try to forget those biases, and remember the following points:

- There is no wizard! Technology isn’t magical. It has specifications that must be respected if you intend to get the desired result.

- If you violate these specifications, in some cases the evidence can actually be evidence of innocence.

- The roads do not become safer by wrongly punishing innocent drivers. Guilty drivers will generally be found guilty, even in a system designed to protect the innocent motorist.

- It is more important to protect the innocent than to convict the guilty.

My argument closely mirrors that of this guy. I guess he won in court, but he’s French so he clearly has an advantage over me.

Here is the certificate (French) for the Mesta 210C speed camera. In the middle of page 2, it is clearly stated that the camera should be oriented at a 25-degree angle to the trajectory of traffic. This relates largely to what is known as the cosine effect, the idea that a car moving away from a radar looks faster than one moving across its beam, however it seems that this particular model has other reasons that make the discrepancy even worse.

Here is an official report from Metz (French) on the impact of improperly aligned cameras on reported speed. At the bottom of page 2, you can see a table showing the effect of small angular error on the reported speed. Note that the effect is very large for even a small deviation from 25 degrees.

Here is a photo from the certificate, taken from a properly configured camera at 25-degree angle from the trajectory of traffic. This angle can be verified with trigonometry (which I have done), but given that it comes from an official document just assume it’s correct.

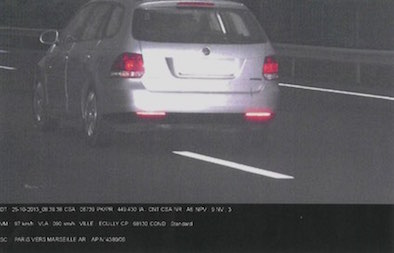

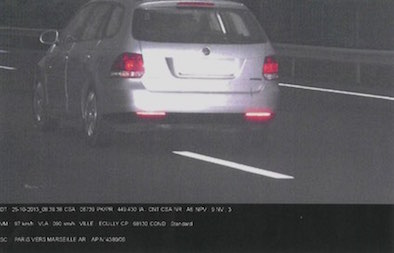

Below is a photo from my ticket. It is easy to see that the car is changing lanes and that this angle is different from that in the other photo. (Disregard the direction of travel, as the system works either way.) Trigonometry shows that this is approximately a 16-degree angle from the camera line of sight, but the difference is also very obvious to the naked eye. This difference in angle is so blatantly obvious that I don’t really need to type anything else to disprove this citation.

Some points to take away from these photos:

- This ticket was issued in clear violation of the 25-degree angle in the camera certificate.

- It is clear to the naked eye that this is true. Anybody who says otherwise has an agenda.

- Based on the French government study linked above, this amount of deviation would lead to speed being over-reported by a lot.

- It is unlikely that vehicle dynamics would allow for crossing lanes at a 9-degree angle while traveling at 97 km/h.

One more note, before I proceed to slam the system. The document regarding the government study stated that it is illegal to operate the camera in violation of the 25-degree rule. This means that the person who sent the ticket might be guilty of a crime.

Due process rights obliterated

The only thing more offensive than being found guilty of the crime, in which any bystander would have seen my innocence, is the complete lack of due process rights along the way. The entire system is set up to be as painful as possible for anybody attempting to challenge a ticket. This includes lost time, lost money, and stress (though, to be fair, this is most government interactions in France). Notice how long this process takes. There is no excuse for this slowness. The system is just incompetent and they probably like it that way, as a deterrent to those who might contest.

The timeline:

- October 25, 2013: “Infraction” committed.

- October 29, 2013: Ticket issued.

- November 2, 2013: I requested photos.

- November 12, 2013: Photos were sent.

- November 21, 2013: I paid EUR 68 “deposit” for the privilege of due process (early payment and admitting guilt would have only been EUR 45).

- December 13, 2013: I sent appeal letter by post.

- December 19, 2013: Notice was sent that file had been transferred to local tribunal de police.

- April 22, 2014: I requested information on the status of the appeal.

- July 1, 2014: Police sent letter requesting me to visit them on July 8 with info about driver’s license. (received on July 6, so limited time window to contact them about rescheduling)

- July 15, 2014: Police meeting. No translator was present, though I had called to request one. Because there was no proof of who was driving, I didn’t need to present my license to get points assigned.

- October 31, 2014: Written appeal rejected. (received several weeks later, but there a clock ticking on the 30-day limit to submit opposition letter)

- November 25, 2014: I appealed the written decision.

- December 19, 2014: I requested all details of the camera configuration via post.

- April 8, 2015 (4 months later!): Response to request for technical details was sent, though it didn’t actually have new information.

- April 27, 2015: I received service to appear in court. I had to go across town to collect this myself.

- April 27, 2015: I requested camera configuration specifications again, but never received response.

- June 3, 2015: Court date.

- June 24, 2015: Notification of decision.

Also note that, in the best case, the cost more than doubles if you fight it. In the worst case, the judge is free to impose a fairly extreme fine. You only fight one of these out of principle. The bureaucrats worked out the math so it’s always a bad financial move to contest, even if you are innocent.

The implications

This should have been a straightforward decision. Anybody can see that the car was changing lanes and it was therefore at an incorrect angle. The prosecutor, Lionel Gauthier, may very well have known his evidence was shaky, as he didn’t put up a serious fight in court. Though he was speaking too fast for my translator, it doesn’t seem that he ever really argued against the actual points I was making. The judge, Sylvie Lagarde, was friendly, but remember that traffic court doesn’t exist in any country to protect the innocent. The translator was nice, but it was her first time in court and she was unable to keep up just due to the nature of the interactions. Nobody was pausing long enough for her to get everything translated. So this alone was pretty unfair. The judge should have taken steps to ensure that every sentence was translated. As it was, 75% of what the prosecutor said was never relayed to me.

This presents a few problems for France:

- This would be a hard enough process for a local to navigate, but successfully challenging a ticket as a foreigner seems impossible. Where is my égalité?

- Because of the translator, I got to go first in court. The translation also meant that my appearance went very slow. It took about 35 minutes. When you have a courtroom of people waiting behind me on this, that has a negative effect on productivity.

- There is a stereotype about French engineering. This ordeal is a data point in support of that. It’s troubling that a ticket with this problem was even mailed out.

- The taxpayers lost money on this case. Yes, they charged me some money to fight it (in clear violation of standard due process principles) but they still didn’t make enough to pay all of the people involved:

- People to process the multiple documents going back and forth,

- Person to rule on written argument,

- One hour of the translator’s time for the court appearance,

- At least 45 minutes of the prosecutor time, and

- At least 45 minutes of the judge’s time.

And you want to know why I recommend against living in France?

But, more seriously: Life is hard. I have a lot of legitimate stresses with respect to moving around and searching for jobs, etc. I want to feel like the government is there to serve the people. I want to feel like the government is there to stand up for the little guy and keep things fair. In general, I’m not anti-government. But when a government behaves like this, victimizing people for no good reason, it’s really upsetting and it leads to a lot of internal conflict about who the government is really there to serve. I know “life isn’t fair,” but in theory aren’t our interactions with the government supposed to be? Are we really supposed to sit back while the government randomly demands our money without any obligation to provide sufficient evidence of wrongdoing?

If the people of France want to reinstate the king’s tax collectors, they should just make it official.

Update (July 15, 2015): I’ve written a detailed description of the math and science behind these problems at https://wheresthecop.com/cosine-effect-and-invalid-photo-citations/.

Fromage

Fromage